An Introduction to Hormone Therapy for Transfeminine People

By Aly | First published August 4, 2018 | Last modified December 17, 2025

Abstract / TL;DR

Sex hormones such as estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone are produced by the gonads. The sex hormones mediate the development of the secondary sexual characteristics. Testosterone causes masculinization, while estradiol causes feminization and breast development. Males have high amounts of testosterone, while females have low testosterone but high amounts of estradiol. These hormonal differences are responsible for the physical differences between males and females. Sex hormones and other hormonal medications are used in transfeminine people to shift the hormonal profile from a male-typical one to a female-typical profile. This causes feminization and demasculinization and allows for alleviation of gender dysphoria. The changes caused by transfeminine hormone therapy occur over a period of months to years. There are many different types and forms of hormonal medications, and these medications can be administered by a variety of different routes. Examples include as pills taken by mouth, as patches or gel applied to the skin, and as injections, among others. Different hormonal medications, routes, and doses have differences in efficacy, side effects, risks, costs, convenience, and availability. Hormone therapy should ideally be regularly monitored in transfeminine people with blood tests to ensure effectiveness and safety and to allow for adjustment as necessary.

The Sex Hormones

Types and Effects

The sex hormones include the estrogens (E), progestogens (P), and androgens. A person’s hormonal profile is a product of the type of gonads that they are born with. Natal males have testes while natal females have ovaries. Testes produce large amounts of androgens and small amounts of estrogens whereas ovaries produce high amounts of estrogens and progesterone and low amounts of androgens.

The major estrogen in the body is estradiol (E2), the main progestogen is progesterone (P4), and the major androgens are testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). The sex hormones are responsible for and determine the secondary sex characteristics. They mediate their effects by acting as agonists (or activators) of receptors inside of cells. These receptors include the androgen receptor (AR), the estrogen receptors (ERs), and the progesterone receptors (PRs). Following their activation, these receptors modulate gene expression to influence cells and tissues.

Estrogens cause feminization. This includes breast development, softening of the skin, a feminine pattern of fat distribution (concentrated in the breasts, hips, thighs, and buttocks), widening of the hips (in those who are still of pubertal age), and other physical changes (Wiki).

Progestogens have essentially no known role in feminization or pubertal breast development. Rather than acting as mediators of feminization, progestogens have important effects in the female reproductive system and are essential hormones during pregnancy (Wiki). They also oppose the actions of estrogens in certain parts of the body, such as the uterus, vagina, and breasts (Wiki).

Androgens cause masculinization. This includes growth of the penis, broadening of the shoulders, expansion of the rib cage, muscle growth, voice deepening, a masculine pattern of fat distribution (concentrated in the stomach and waist), masculine changes in other soft tissues, and facial/body hair growth (Wiki). Androgens also cause a variety of generally undesirable skin and hair effects, including oily skin, acne, seborrhea, scalp hair loss, and body odor. They additionally oppose breast development and probably other aspects of feminization mediated by estrogens as well.

In addition to their effects on the body, sex hormones have actions in the brain. These actions influence cognition, emotions, and behavior. For instance, androgens produce pronounced sexual desire and arousal (including spontaneous erections) in men, while estrogens appear to be the major hormones responsible for sexual desire in women (Cappelletti & Wallen, 2016). As another example, testosterone levels have been negatively associated with agreeableness, whereas estrogen levels have been positively associated with this characteristic (Treleaven et al., 2013). Sex hormones also have important effects on health, which can be both positive and negative. For instance, estrogens maintain bone strength and likely protect against heart disease in cisgender women (NAMS, 2022), but also increase the risk of breast cancer (Aly, 2020) and can increase the risk of blood clots (Aly, 2020).

Estrogens, progestogens, and androgens also have antigonadotropic effects. That is, they inhibit the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-induced secretion of the gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), from the pituitary gland in the brain. The gonadotropins signal the gonads to make sex hormones and to supply the sperm and egg cells necessary for fertility. Hence, lower levels of the gonadotropins will result in reduced gonadal sex hormone production and diminished fertility. If gonadotropin levels are sufficiently suppressed, the gonads will no longer make sex hormones at all and fertility will cease. The vast majorities of the quantities of estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone in the body are produced by the gonads. Most of the small remaining amounts of these hormones are produced via the adrenal glands of the kidneys.

Normal Hormone Levels

In cisgender females, the sex hormones are largely absent during childhood, gradually ramp up in production in late childhood and adolescence, are present in a cyclical manner during adulthood, and then largely stop being produced following the menopause. Hormone levels vary substantially but in a predictable manner during the normal menstrual cycle in adult premenopausal women. The menstrual cycle lasts about 28 days on average and consists of the following parts:

- Follicular phase—first half of the cycle or days 1–14

- Mid-cycle—middle of the cycle or days 12–16 or so

- Luteal phase—latter half of the cycle or days 14–28

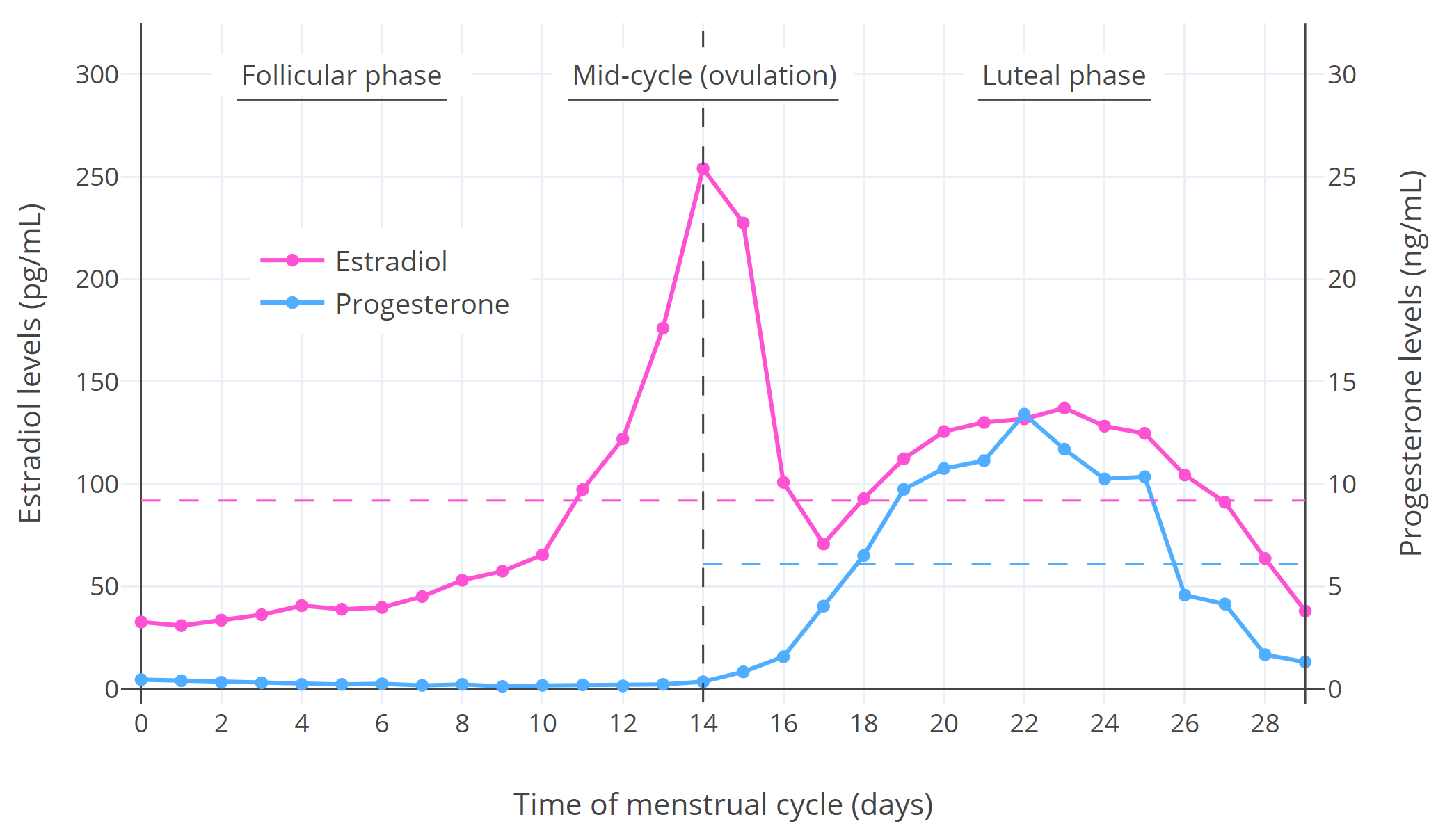

Hormone levels during the menstrual cycle are shown in the following graph:

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Median estradiol and progesterone levels throughout the menstrual cycle in premenopausal cisgender women (Stricker et al., 2006; Abbott, 2009). The horizontal dashed lines are the average levels over the spanned periods. Other figures available elsewhere show variation between individuals (Graph; Graph; Graph). |

As can be seen in the graph, estradiol levels are relatively low and progesterone levels are very low during the follicular phase; estradiol but not progesterone levels briefly surge to very high levels and trigger ovulation during mid-cycle; and estradiol and progesterone levels both undergo a bump and are relatively high during the luteal phase (though estradiol is not as high as during the mid-cycle peak).

The table below shows the circulating levels and production rates of estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone in women and men and allows for comparison between them.

Table 1: Ranges for circulating levelsa and estimated production ratesb of the major sex hormones:

| Hormone | Group | Time | Levels (mass/vol)c | Levels (mol/vol)c | Production rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | Womend | Follicular phase | 5–180 pg/mL | 20–660 pmol/L | 30–170 μg/daye |

| Mid-cycle | 45–750 pg/mL | 170–2,750 pmol/L | 320–950 μg/daye | ||

| Luteal phase | 20–300 pg/mL | 73–1100 pmol/L | 250–300 μg/daye | ||

| Men | – | 8–35 pg/mL | 30–130 pmol/L | 10–60 μg/day | |

| Progesterone | Womend | Follicular phase | ≤0.3 ng/mL | ≤1.0 nmol/L | 0.75–5 mg/day |

| Mid-cycle | 0.1–1.5 ng/mL | 0.3–4.8 nmol/L | 4 mg/day | ||

| Luteal phase | 3.5–38 ng/mL | 11–120 nmol/L | 15–50 mg/dayf | ||

| Men | – | ≤0.5 ng/mL | ≤1.6 nmol/L | 0.75–3 mg/day | |

| Testosterone | Womend | Menstrual cycle | 5–55 ng/dL | 0.2–1.9 nmol/L | 190–260 μg/day |

| Men | – | 250–1100 ng/dL | 8.7–38 nmol/L | 5–7 mg/day |

a Sources for hormone levels: Zhang & Stanczyk (2013); Nakamoto (2016); Styne (2016); LabCorp (2020). b Sources for production rates: Aufrère & Benson (1976); Powers et al. (1985); Lauritzen (1988); Carr (1993); O’Connell (1995); Kuhl (2003); Norman & Henry (2015a); Norman & Henry (2015b); Strauss & FitzGerald (2019). c With liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) (state-of-the-art blood tests). d During the menstrual cycle in the adult premenopause (age ~18–50 years). e Average production rate of estradiol over the whole menstrual cycle is roughly 200 μg/day or 6 mg/month (Rosenfield, Cooke, & Radovich, 2021). f Average production rate of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle is about 25 mg/day (Carr, 1993).

Mean integrated estradiol levels are around 100 pg/mL (367 pmol/L) in premenopausal women and around 25 pg/mL (92 pmol/L) in men. The 95% range for mean estradiol levels in women is around 50 to 250 pg/mL (180–918 pmol/L) (e.g., Abbott, 2009 (Graph); Verdonk et al., 2019 (Graph)). The average production of estradiol by the ovaries in premenopausal women is about 6 mg over the course of one menstrual cycle (i.e., one month) (Rosenfield et al., 2008). This corresponds to a mean rate of about 200 μg/day. Estradiol levels increase slowly during normal female puberty, when breast development and feminization take place. Mean estradiol levels during the different stages of female puberty are quite low—less than about 50 to 60 pg/mL (180–220 pmol/L) until late puberty (Aly, 2020). In postmenopausal women, whose ovaries no longer produce considerable quantities of estrogens, estradiol levels are generally less than 10 to 20 pg/mL (37–73 pmol/L) (Nakamoto, 2016). Estradiol levels below 50 pg/mL (184 pmol/L) in adults are concentration-dependently associated with menopausal symptoms, including hot flashes, depressive mood changes, defeminization (e.g., breast atrophy, loss of feminine fat distribution), accelerated skin aging, and bone density loss with increased risk of bone fracture.

Mean testosterone levels are around 30 ng/dL (1.0 nmol/L) in women and 600 ng/dL (21 nmol/L) in men. Based on these values, testosterone levels are on average about 20-fold higher in men than in women. In men who have undergone gonadectomy (castration or surgical gonadal removal), testosterone levels are similar to those in women (<50 ng/dL [1.7 nmol/L]) (Nishiyama, 2014; Getzenberg & Itty, 2020). The mean or median levels of testosterone in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), who often have clinically significant symptoms of androgen excess (e.g., excessive facial/body hair growth), range from 41 to 75 ng/dL (1.4–2.6 nmol/L) per different studies (Balen et al., 1995; Steinberger et al., 1998; Legro et al., 2010; Loh et al., 2020). Hence, it appears that even testosterone levels that are marginally elevated relative to normal female levels may produce undesirable androgenic effects.

It is important to be aware that measurement of hormone levels is subject to methodological limitations, and hormone levels vary significantly when quantified by different methods and laboratories on account of varying assay accuracy (Shackleton, 2010; Stanczyk & Clarke, 2010; Deutsch, 2016; Carmina, Stanczyk, & Lobo, 2019). Mass spectrometry (MS)-based assays, such as liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), are regarded as more accurate and reliable than immunoassay (IA)-based assays, such as radioimmunoassays (RIA) and direct immunoassays like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (Stanczyk & Clarke, 2010; Carmina, Stanczyk, & Lobo, 2019). In relation to this, MS-based tests are gradually becoming the standard for laboratory testing of sex hormone levels. However, hormone levels vary between laboratories even with LC–MS, for instance due to differences in calibration of LC–MS instruments between laboratories (Carmina, Stanczyk, & Lobo, 2019). Whereas an accurate range for testosterone levels in cisgender women is 20 to 50 ng/dL (0.69–1.7 nmol/L), for instance with assays like RIA and LC–MS, the normal upper limit for direct immunoassays like ELISA may be 70 to 80 ng/dL (2.4–2.8 nmol/L) (Carmina, Stanczyk, & Lobo, 2019). When interpreting blood tests, care should be taken to compare sex hormone levels to same-laboratory reference ranges (Deutsch, 2016).

Overview of Hormone Therapy

The goal of hormone therapy for transfeminine people, otherwise known as feminizing hormone therapy (FHT) or (more in the past) as male-to-female (MtF) hormone replacement therapy (HRT), is to produce feminization and demasculinization of the body as well as alleviation of gender dysphoria. Medication therapy with sex hormones and other sex-hormonal medications is used to mediate these changes. Transfeminine people are given estrogens, progestogens, and antiandrogens (AAs) to supersede gonadal sex hormone production and shift the hormonal profile from male-typical to female-typical.

Transfeminine hormone therapy aims to achieve estradiol and testosterone levels within the normal female range. Commonly recommended ranges for transfeminine people in the literature are 100 to 200 pg/mL (367–734 pmol/L) for estradiol levels and less than 50 ng/dL (1.7 nmol/L) for testosterone levels (Table). However, higher estradiol levels of more than 200 pg/mL (734 pmol/L) can be useful in transfeminine hormone therapy to help suppress testosterone levels. Lower estradiol levels (≤50–60 pg/mL [≤180–220 pmol/L]) are recommended and more appropriate for pubertal and adolescent transfeminine individuals. Sex hormone levels in the blood can be measured with blood tests, in which blood is drawn from a vein using a needle and then analyzed in a laboratory. This is useful in transfeminine people to ensure that the hormonal profile has been satisfactorily altered in line with therapeutic goals—specifically that hormone levels are within female ranges.

Gonadal Suppression

At sufficiently high exposure, estrogens and androgens are able to completely suppress gonadal sex hormone production, while progestogens by themselves are able to partially but substantially suppress gonadal sex hormone production. More specifically, studies in cisgender men and transfeminine people have found that estradiol levels of around 200 pg/mL (734 pmol/L) suppress testosterone levels by about 90% on average (to ~50 ng/dL [1.7 nmol/L]), while estradiol levels of around 500 pg/mL (1,840 pmol/L) suppress testosterone levels by about 95% on average (to ~20–30 ng/dL [0.7–1.0 nmol/L]) (Gooren et al., 1984 [Graph]; Herndon et al., 2023 [Discussion]; Wiki; Graphs). Estradiol levels of below 200 pg/mL (734 pmol/L) also suppress testosterone levels, although to a reduced extent compared to higher levels (Aly, 2019; Krishnamurthy et al., 2023; Slack et al., 2023). In one large study in transfeminine people, the rates of adequate testosterone suppression (to testosterone levels of <50 ng/dL or <1.7 nmol/L) were 24% of individuals at estradiol levels of <100 pg/mL (367 pmol/L), 58% at 100 to 200 pg/mL (367–734 pmol/L), and 77% at >200 pg/mL (>734 pmol/L) (Krishnamurthy et al., 2023).

|

|---|

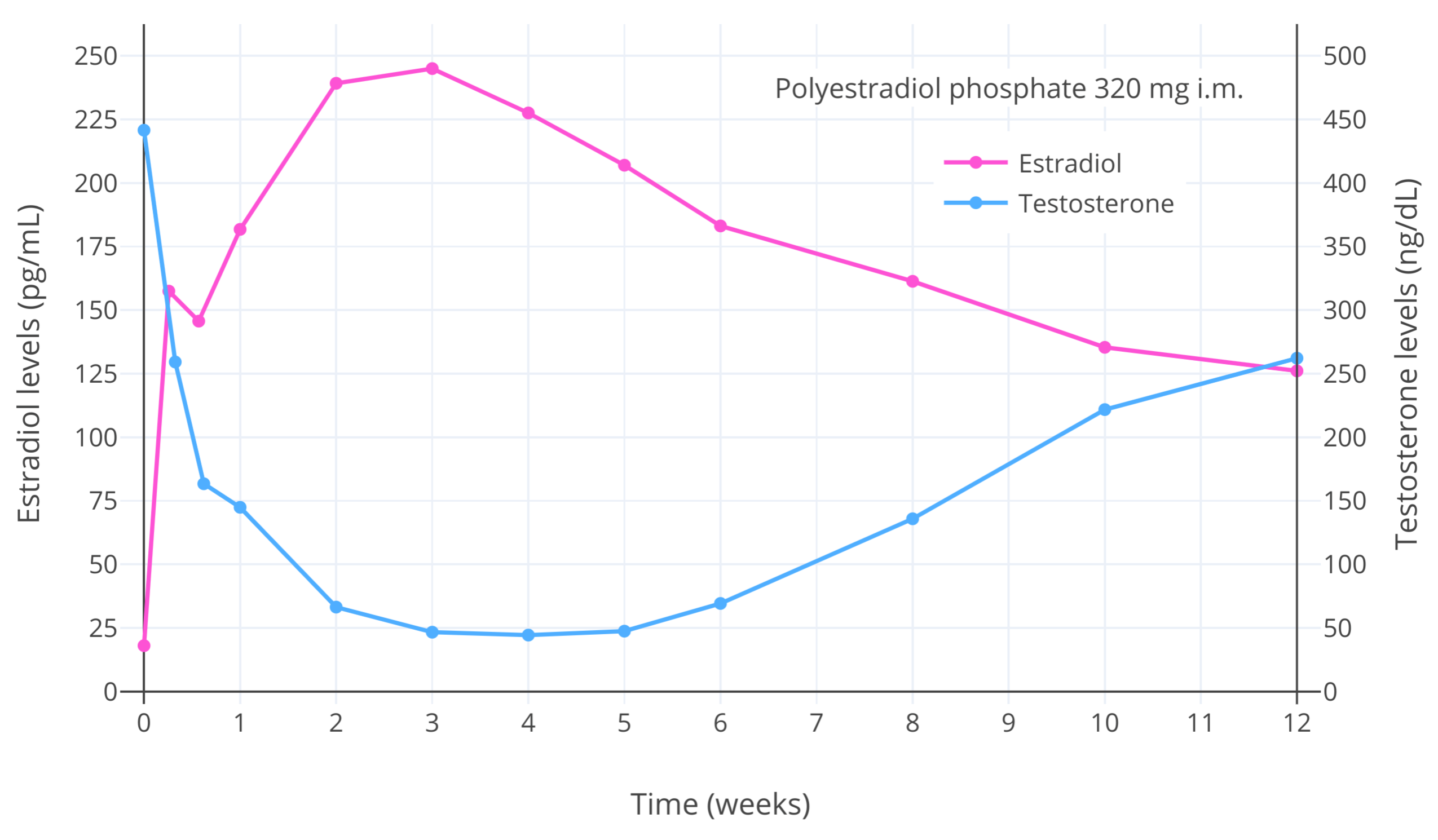

| Figure 2: Estradiol and testosterone levels after a single injection of 320 mg polyestradiol phosphate (PEP) (a long-acting prodrug of estradiol) in men with prostate cancer (Stege et al., 1996). The maximal decrease in testosterone levels occurred with estradiol levels of greater than 200 pg/mL (734 pmol/L) and was about 90% (to roughly 50 ng/dL [1.7 nmol/L]). This figure demonstrates the ability of estradiol to concentration-dependently suppress gonadal testosterone production and circulating testosterone levels in people with testes. |

Progestogens on their own are able to maximally suppress testosterone levels by about 50 to 70% (to ~150–300 ng/dL [5.2–10.4 nmol/L] on average) (Aly, 2019; Wiki). In combination with relatively small amounts of estrogen however, there is synergism in the antigonadotropic effect—the suppression of gonadal testosterone production with maximally effective doses of progestogens becomes complete, and testosterone levels are reduced by about 95% (to ~20–30 ng/dL [0.7–1.0 nmol/L]) (Aly, 2019). Hence, the combination of an estrogen and a progestogen can be used to achieve maximal testosterone suppression at lower doses than would be necessary if an estrogen or progestogen were used alone.

The antigonadotropic effects of estrogens and progestogens are taken advantage of in transfeminine hormone therapy to suppress gonadal testosterone production and attain testosterone levels that are more consistent with those in cisgender women. It should be noted that the preceding numbers on testosterone suppression with estrogens and progestogens are averages and there is significant variation between individuals in terms of testosterone suppression. In other words, some may need more or less in terms of hormonal dosages to achieve the same decrease in testosterone levels.

Effects and Timeline

During normal puberty in both males and females, sex hormone exposure increases slowly over a period of several years (Aly, 2020). In relation to this, sexual maturation occurs gradually during normal puberty. In non-adolescent transgender people, adult or higher amounts of hormones are generally administered right away, and this can result in changes in secondary sex characteristics happening more quickly. Most of the effects of feminizing hormone therapy in transfeminine people onset within 1 to 6 months of commencing treatment and complete within 1 to 3 years. The table below is reproduced from literature sources with slight modification and is commonly cited as a timeline of the effects (Table). It is based on a mixture of anecdotal clinical experience, expert opinion, and available clinical studies of hormone therapy in transfeminine people. Due to limited research characterizing the effects of transfeminine hormone therapy at present, the table may or may not be completely accurate.

Table 2: Effects of hormone therapy at typical doses in adult transfeminine people (Wiki):

| Effect | Onseta | Completiona | Permanency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast development | 2–6 months | 2–3 years | Permanent |

| Reduced and slowed growth of facial and body hair | 3–12 months | >3 yearsb | Reversible |

| Cessation and reversal of scalp hair loss | 1–3 months | 1–2 years | Reversible |

| Softening of skin and decreased skin oiliness and acne | 3–6 months | Unknown | Reversible |

| Redistribution of body fat in a feminine pattern | 3–6 months | 2–5 years | Reversible |

| Decreased muscle mass and strength | 3–6 months | 1–2 yearsc | Reversible |

| Widening and rounding of the pelvisd | Unknown | Unknown | Permanent |

| Changes in mood, emotionality, and behavior | Immediate | Unknown | Reversible |

| Decreased sex drive and spontaneous erections | 1–3 months | 3–6 months | Reversible |

| Erectile dysfunction and decreased ejaculate volume | 1–3 months | Variable | Reversible |

| Decreased sperm production and infertility | Unknown | >3 years | Mixede |

| Decreased testicular volume | 3–6 months | 2–3 years | Unknown |

| Voice changes (e.g., more feminine pitch/resonance) | Nonef | N/A | N/A |

| Height changes (e.g., decrease) | Noneg | N/A | N/A |

a Effects in general may vary significantly between individuals due to factors like genetics, diet/nutrition, hormone levels, etc. b Hormone therapy usually has little influence on facial hair density in transfeminine people. Complete removal of facial and body hair can be achieved with laser hair removal and electrolysis. Temporary hair removal can be achieved with shaving, epilating, waxing, and other methods. c Reduced muscle mass and strength may vary significantly depending on amount of physical exercise. d Pelvic changes occur only in young individuals who have not yet completed growth plate closure (may not occur at all in post-adolescent people). e Only estrogens, particularly at high doses, seem to have the potential for long-lasting or irreversible infertility; impaired fertility caused by antiandrogens is usually readily reversible with discontinuation. f Voice training can be an effective means of feminizing the voice. g Height attainment may be reduced in adolescents, but height is not meaningfully changed or reduced in adults per clinical data (Gooren & Bunck, 2004; Ingram & Thomas, 2019; Hilton & Lundberg, 2020; Talathi et al., 2025).

Breast Development

Breast development is among the most anticipated effects of hormone therapy in transfeminine people (Masumori et al., 2021; Grock et al., 2024). This relates to the key significance of breasts as a feminine characteristic, component of sexual attractiveness, and signal of sex and gender. Breast growth in transfeminine people usually starts within 1 to 6 months and completes over a period of 1 to 3 years (e.g., de Blok et al., 2021). The developed breasts of transfeminine people are highly variable in terms of size and shape, as with natal women (de Blok et al., 2021). Based on available high-quality clinical studies, transfeminine people tend to have much smaller mature breasts than those of natal women on average, and this appears to be the case regardless of hormonal regimen or age at which hormone therapy is commenced (e.g., de Blok et al., 2021; Boogers et al., 2025). The reasons for this are unknown, but one key possibility, observed in animals, is that prenatal androgen exposure limits subsequent breast growth potential. Despite usually modest breast development, many transfeminine people still express overall satisfaction with their breasts (de Blok et al., 2021; Boogers et al., 2025).

Beyond ensuring adequate testosterone suppression and maintaining sufficient estradiol levels above a specific low threshold, there are currently no known or substantiated methods to permanently enhance or optimize breast development. However, research suggests that avoiding high or excessive doses of estradiol and progestogens may be beneficial. In addition, high levels of estradiol, progesterone, and/or prolactin, as with the normal menstrual cycle and pregnancy, are known to induce temporary and reversible breast tenderness and enlargement, for instance due to local fluid retention and lobuloalveolar maturation (Aly, 2020). However, the breast size increases are modest, and high hormone levels come with health risks (Aly, 2020). Surgical breast augmentation is an option to increase breast size if it is unsatisfactory. Some transfeminine people, for instance many non-binary individuals, may wish to avoid or minimize breast growth, and there are possible therapeutic approaches in this area (Aly, 2019).

Additional review content on breast development in transfeminine people exists on this site (e.g., Aly, 2020; Aly, 2020). Breast growth can be measured and tracked with a variety of methods for individuals who are interested in monitoring their progress (Wiki). Photographs and timelines of breast development and feminization with hormone therapy in transfeminine people are available in communities like r/TransTimelines and r/TransBreastTimelines on the social media website Reddit.

Specific Hormonal Medications

The medications that are used in transfeminine hormone therapy include estrogens, progestogens, and antiandrogens. Estrogens produce feminization and testosterone suppression. Progestogens and antiandrogens do not mediate feminization themselves but further suppress and/or block testosterone. Testosterone suppression causes demasculinization and disinhibition of estrogen-mediated feminization. Androgens are sometimes used at low doses in transfeminine people who have low testosterone levels, although they are not required and benefits are uncertain. There are many different types of these hormonal medications available for transfeminine hormone therapy, with different benefits and risks.

Estrogens, progestogens, and antiandrogens are available in a variety of different formulations and for use by many different routes of administration in transfeminine people. The route of administration influences the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of the hormone in the body, resulting in significant differences between routes in terms of bioavailability, hormone levels in blood and specific tissues, and patterns of metabolites. These differences can have important therapeutic consequences.

Table 3: Major routes of administration of hormonal medications for transfeminine people:

| Route | Abbr. | Description | Typical forms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral administration | PO | Swallowed | Tablet, capsule |

| Sublingual administration | SL | Held and absorbed under tongue | Tablet |

| Buccal administration | BUC | Held and absorbed in cheek or under lips | Tablet |

| Transdermal administration | TD | Applied to and absorbed through the skin | Patch, gel, cream |

| Rectal administration | REC | Inserted into and absorbed by rectum | Suppository |

| Intramuscular injection | IM | Injected into muscle (e.g., buttocks, thigh, arm) | Solution (vial/amp.) |

| Subcutaneous injection | SC | Injected into fat under skin | Solution (vial/amp.) |

| Subcutaneous implant | SCi | Insertion via surgical incision into fat under skin | Pellet |

Vaginal administration is a major additional route of administration of hormonal medications in cisgender women. While vaginal administration via a natal vagina is of course not possible in transfeminine people, neovaginal administration is a possiblility in those who have undergone vaginoplasty. However, the lining of the neovagina is not the vaginal epithelium of natal females but instead is usually skin or colon—depending on the type of vaginoplasty performed (penile inversion or sigmoid colon vaginoplasty, respectively). For this reason, neovaginal administration in transfeminine people is likely more similar in its properties to transdermal and rectal administration—depending on the type of neovagina—than to vaginal administration in cisgender women. It is noteworthy that the vaginal and rectal routes are said to be similar in their properties for hormonal medications however (Goletiani, Keith, & Gorsky, 2007; Wiki). Moreover, absorption of estradiol via neovaginas constructed from peritoneum (internal abdominal lining)—a less commonly employed vaginoplasty approach in transfeminine people—was reported in one study to be similar to that with vaginal administration of estradiol in cisgender women (Willemsen et al., 1985). As such, neovaginal administration may be an additional possible route for certain transfeminine people depending on the circumstances. However, this route still remains to be more adequately characterized.

An often-encountered question from people who take hormonal medications is whether there is an optimal time of the day to take them (Colonnello et al., 2025). As of present, there is little research in this area, and the answer to the question is essentially unknown (Colonnello et al., 2025). In any case, there is currently no evidence or persuasive theoretical basis to favor specific times of day to take these medications (Colonnello et al., 2025). In all likelihood, it makes little or no difference.

Estrogens

Estradiol, the primary bioidentical form normally found in the human body, is the main estrogen that is used in transfeminine hormone therapy. Estradiol hemihydrate (EH) is another form that is essentially identical to and interchangeable with estradiol. Estradiol esters are also sometimes used in place of estradiol. They are prodrugs of estradiol (i.e., are converted into estradiol in the body) and have essentially identical biological activity to estradiol. However, they have longer durations when used by injection due to slower absorption from the injection site, and this allows them to be administered less often. Some examples of major estradiol esters include estradiol valerate (EV; Progynova, Progynon Depot, Delestrogen) and estradiol cypionate (EC; Depo-Estradiol). Polyestradiol phosphate (PEP; Estradurin) is an injectable estradiol prodrug in the form of a polymer (i.e., linked chain of estradiol molecules) which is metabolized slowly and has a very long duration.

Non-bioidentical estrogens such as ethinylestradiol (EE; found in birth control pills), conjugated estrogens (CEEs; Premarin; used in menopausal hormone therapy), and diethylstilbestrol (DES; widely used previously but now abandoned) are resistant to metabolism in the liver and have disproportionate effects on estrogen-modulated liver synthesis when compared to bioidentical estrogens like estradiol (Aly, 2020). As a result, they have stronger influence on coagulation and greater risk of certain health problems like blood clots and associated cardiovascular issues (Aly, 2020). For this reason, as well as the fact that relatively high doses of estrogens may be needed for testosterone suppression, non-bioidentical estrogens should ideally never be used in transfeminine hormone therapy.

Estradiol dose-dependently suppresses testosterone levels in people with testes. Physiological and guideline-based levels of estradiol (<200 pg/mL or <734 pmol/L) are often not sufficient to suppress testosterone levels into the female range in transfeminine people who have not had their gonads removed (e.g., Liang et al., 2018; Krishnamurthy et al., 2023; Slack et al., 2023). As a result, estradiol is generally used in combination with an antiandrogen or progestogen in transfeminine hormone therapy (Hembree et al., 2017; Coleman et al., 2022; Rose et al., 2023). This results in partial suppression of testosterone levels by estradiol and further suppression or blockade of the remaining testosterone by the antiandrogen or progestogen. While combination therapy can be effective in fully suppressing or blocking testosterone (e.g., Aly, 2019; Aly, 2020), testosterone suppression can also still remain incomplete with antiandrogens and progestogens in certain forms (e.g., Aly, 2018; Jain, Kwan, & Forcier, 2019). In contrast to physiological estradiol levels, supraphysiological levels of estradiol are able to consistently and fully suppress testosterone levels into the normal female range with estradiol alone in transfeminine people (e.g., Gooren et al., 1984 [Graph]; Igo & Visram, 2021; Herndon et al., 2023 [Discussion]). This alternative approach, often referred to as high-dose estradiol monotherapy, has the advantage of avoiding the side effects, risks, and costs of antiandrogens and progestogens. However, it has the disadvantage of exposure to supraphysiological estradiol levels that are above those recommended by guidelines and that may have greater health risks. Physiological estradiol doses and combination therapy are more often used in transfeminine people treated by clinicians, whereas high-dose estradiol monotherapy is more frequently encountered in transfeminine people on DIY hormone therapy.

The feminizing effects of estradiol appear to be maximal at relatively low levels in the absence of androgens. Higher doses of estradiol and supraphysiological estradiol levels, aside from allowing for greater testosterone suppression, are not known to result in better feminization in transfeminine people (Deutsch, 2016; Nolan & Cheung, 2021). In fact, there is some indication that higher estrogen doses early into hormone therapy could actually result in worse breast development. Hence, the therapeutic emphasis in transfeminine hormone therapy is more on testosterone suppression than on achieving a specific estradiol level, at least above a certain low threshold level. Higher doses of estrogens, including of estradiol, also have a greater risk of adverse health effects such as blood clots and cardiovascular problems (Aly, 2020). As such, the use of physiological doses of estradiol is optimal in transfeminine people. At the same time however, high estrogen doses can be useful for improving testosterone suppression when it is inadequate, and the absolute risks, in the case of non-oral bioidentical estradiol, are low and are more important in people with specific risk factors (e.g., older age, physical inactivity, obesity, concomitant progestogen use, smoking, surgery, and rare thrombophilic abnormalities). If more adequate testosterone suppression is necessary, limitedly supraphysiological doses of non-oral estradiol may have a reasonable ratio of benefit to risk in this context, at least in those without relevant risk factors for estrogen-related complications (e.g., many healthy young people) (Aly, 2020).

Estradiol and estradiol esters are usually used orally, sublingually, transdermally, by injection (intramuscularly or subcutaneously), or by implant in transfeminine hormone therapy (Wiki).

Oral Estradiol

Estradiol is used orally in the form of tablets of estradiol (Wiki; Graphs). Alternatively, oral estradiol valerate tablets are used in some countries, for instance in many European countries. The only real difference between these oral estradiol forms is that estradiol valerate contains slightly less estradiol by weight (~76% of that of estradiol) due to its ester component and hence requires somewhat higher doses (~1.3-fold) in comparison for equivalent estradiol levels (Wiki; Table). Oral estradiol has a duration suitable for once-daily administration. Oral administration of estradiol is a very convenient and inexpensive route, which makes it the most popular and widely used form of estradiol in transfeminine people. Oral estradiol has relatively low bioavailability (~5%), and there is substantial variability between people in terms of estradiol levels achieved with the same dose. Hence, in some transfeminine people estradiol levels may be low with oral estradiol, and testosterone suppression may be inadequate depending on the antiandrogen.

A major drawback of oral estradiol is that it results in excessive levels of estradiol in the liver due to the first pass that occurs with oral administration and has a disproportionate impact on estrogen-modulated liver synthesis (Aly, 2020). This in turn increases coagulation and the risk of associated health complications like blood clots and cardiovascular problems (Aly, 2020). These particular health concerns are largely allayed if estradiol is taken non-orally at reasonable and non-excessive doses. Hence non-oral forms of estradiol, like transdermal estradiol, although less convenient and often more expensive than oral estradiol, are preferable in transfeminine hormone therapy. It is recommended that all transfeminine people who are over 40 to 45 years of age use non-oral routes due to the greater risk of blood clots and cardiovascular problems that occurs with age (Aly, 2020; Coleman et al., 2022). Oral estradiol is not a good choice for high-dose estradiol monotherapy in transfeminine people due to the high estradiol levels required and the greater risks than with non-oral routes. In addition to its disproportionate liver impact, oral estradiol results in unphysiological levels of estradiol metabolites like estrone and estrone sulfate when compared to non-oral forms. The clinical implications of this, if any, are unknown. Oral and non-oral estradiol have in any case been found to have similar effectiveness in terms of feminization and breast development in transfeminine people in available studies (Sam, 2020).

Sublingual Estradiol

Oral estradiol tablets can be taken sublingually instead of orally. Sublingual use of estradiol tablets has several-fold higher bioavailability relative to oral administration and hence achieves much higher overall estradiol levels in comparison (Sam, 2021; Wiki; Graphs). Sublingual use of oral estradiol tablets can be employed instead of oral administration to reduce doses and hence medication costs or to produce higher estradiol levels for the purpose of achieving better testosterone suppression when needed. However, sublingual estradiol is very spiky in terms of estradiol levels when compared to oral estradiol and has a short duration of highly elevated estradiol levels. As such, it may be advisable for sublingual estradiol to be used in divided doses multiple times throughout the day in order to maintain at least somewhat steadier estradiol levels. The therapeutic implications for transfeminine people of the spikiness of sublingual estradiol, for instance in terms of testosterone suppression and health risks, have been little-studied and are mostly unknown. In any case, when used as a form of high-dose estradiol monotherapy and taken multiple times per day, strong though still incomplete testosterone suppression has been observed (Yaish et al., 2023). Oral estradiol valerate tablets can be taken sublingually instead of orally similarly to estradiol and are likewise highly effective when used in this way (Aly, 2019; Wiki). Due to partial swallowing of tablets, sublingual estradiol may in practice be a mixture of sublingual and oral administration and may have some of the same health risks of oral estradiol (Wiki). Buccal administration of estradiol appears to have similar properties as sublingual administration but is much less researched in comparison and is not used as often in transfeminine people (Wiki).

Transdermal Estradiol

Transdermal estradiol is available in the form of patches, gel, emulsions, and sprays (Wiki). These forms are usually applied to skin areas such as the arms, abdomen, or buttocks. Gel, emulsions, and sprays are applied and left to dry for a short period, whereas patches are applied and remain adhesed to the skin for a specified amount of time. Due to rate-limited absorption through the skin, there is a depot effect with transdermal estradiol and this route has a long duration with very steady estradiol levels. As a result, estradiol gel, emulsions, and sprays are all suitable for once-daily use. Patches stay applied and continuously deliver estradiol for either 3–4 days or 7 days depending on the patch brand (Table). Transdermal estradiol is more expensive than oral estradiol. Gel, emulsions, and sprays may be less convenient than oral administration, but patches can be more convenient due to their infrequent application. However, patches can sometimes cause application site problems like redness and irritation and can occasionally come off prematurely due to adhesive failure. As with oral estradiol, there is substantial variability in estradiol levels with transdermal estradiol, and some transfeminine people may have poor absorption, low estradiol levels, and inadequate testosterone suppression with this route. Estradiol sprays, such as Lenzetto, have been found to achieve very low estradiol levels that are probably not therapeutically adequate for use in transfeminine hormone therapy (Aly, 2020; Graph).

Transdermal estradiol is the form of estradiol most commonly used in transfeminine people who are over 40 years of age due to its lower health risks relative to oral estradiol. Transdermal estradiol gel is not a favorable option for high-dose estradiol monotherapy as it has difficulty achieving the high estradiol levels needed for adequate testosterone suppression (Aly, 2019). On the other hand, transdermal estradiol patches can be an effective option for high-dose estradiol monotherapy if multiple 100 μg/day patches are used, although this can require the use of many patches and can be expensive (Wiki). Different skin sites absorb transdermal estradiol to different extents (Wiki). Genital application of transdermal estradiol, specifically to the scrotum or neolabia, is particularly better-absorbed than conventional skin sites and can result in much higher estradiol levels than usual (Aly, 2019). This can be useful for reducing doses and hence medication costs or for achieving higher estradiol levels for better testosterone suppression when needed, for instance in the context of high-dose estradiol monotherapy. Transdermal estradiol should not be applied to the breasts as this is not known to result in improved breast development and the potential health consequences of doing so are unknown (e.g., influence on breast cancer risk).

Injectable Estradiol

Injectable estradiol preparations can be administered via either intramuscular or subcutaneous injection (Wiki; Wiki; Graphs). There is a depot effect with injection of estradiol esters such that they are slowly absorbed from the injection site and have a prolonged duration. This ranges from days to months depending on the ester. Commonly used injectable estradiol esters, which all have short to moderate durations, include estradiol valerate (EV), estradiol cypionate (EC), estradiol enanthate (EEn), and estradiol benzoate (EB). Longer-acting injectable estradiol esters, such as estradiol undecylate (EU) and polyestradiol phosphate (PEP), have been discontinued and are no longer pharmaceutically available. In the case of intramuscular injection, common injection sites include the deltoid muscle (upper arm), vastus lateralis and rectus femoris muscles (thigh), and ventrogluteal muscle (buttocks). Subcutaneous injection of estradiol injectables, while less commonly used, has comparable pharmacokinetics to intramuscular injection, and is easier, less painful, and more convenient in comparison (Wiki). However, the maximum volume that can be safely and comfortably injected subcutaneously (1.5–3 mL) is less than that which can be injected intramuscularly (2–5 mL) (Hopkins, & Arias, 2013; Usach et al., 2019). Injectable estradiol tends to be fairly inexpensive, but may be less convenient than other routes due to the need for regular injections. There may also be a risk of internal scar tissue build-up long-term. Estradiol injectables have been discontinued in many parts of the world (e.g., most of Europe), and their availability is limited. In recent years, many transfeminine people have turned to black market homebrewed injectable estradiol preparations to use this route.

Injectable estradiol preparations are typically used at higher doses than other forms of estradiol, and can easily achieve very high levels of estradiol. This can be useful for testosterone suppression, making this form of estradiol likely the best choice for high-dose estradiol monotherapy in transfeminine people. However, the high doses that are possible with injectable estradiol preparations can also easily lead to overdosage and unnecessarily increased risks (e.g., Aly, 2020). Resources are available on this site for guiding selection of appropriate doses and intervals of injectable estradiol esters in transfeminine people. This includes a simulator and informal meta-analysis of estradiol levels with these preparations (Aly, 2021; Aly, 2021) and a table providing approximate equivalent doses between injectable estradiol esters and other estradiol routes and forms (Aly, 2020). It is notable and unfortunate that currently recommended doses and intervals for injectable estradiol esters by transgender care guidelines (e.g., 10–40 mg/2 weeks estradiol valerate) appear to be highly excessive and too widely spaced, and are likely to be therapeutically inadvisable (Aly, 2021). Doses and intervals of injectable estradiol esters recommended by the present author for use as a means of high-dose estradiol monotherapy, targeting mean estradiol levels of around 300 pg/mL (1,100 pmol/L), are provided below (Table 4).

Table 4: Recommended doses and intervals of injectable estradiol esters for high-dose estradiol monotherapy (targeting estradiol levels of around 300 pg/mL [1,100 pmol/L]):

| Estradiol Ester | Shorta | Mediuma | Longa | Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol benzoate | 0.67 mg/1 day | 1.33 mg/2 days | 2 mg/3 days | Graph |

| Estradiol valerate | 2 mg/3 days | 3.5 mg/5 days | 5 mg/7 days | Graph |

| Estradiol cypionate (in oil) | 5 mg/7 days | 7 mg/10 days | 10 mg/14 days | Graph |

| Estradiol cypionate (suspension) | 2 mg/3 days | 3.5 mg/5 days | 5 mg/7 days | Graph |

| Estradiol enanthate | 5 mg/7 days | 7 mg/10 days | 10 mg/14 days | Graph |

| Estradiol undecylateb | 10 mg/14 days | 20 mg/28 days | 30 mg/42 days | Graph |

| Polyestradiol phosphate | 160 mg/30 days | 240 mg/45 days | 320 mg/60 days | Graph |

a Injection interval. b Doses and intervals for estradiol undecylate are extrapolated and hypothetical (Aly, 2021).

These doses and intervals should be considered a starting point, and should be fine-tuned as necessary based on blood tests. In terms of injection intervals, the shorter interval, the more stable the estradiol levels, but the more often that injections need to be done. Doses may be increased if estradiol levels are too low and testosterone suppression is inadequate, and doses may be decreased if estradiol levels are too high so long as adequate testosterone suppression is maintained. Doses should be lower (targeting mean estradiol levels of 100–200 pg/mL [367–734 pmol/L]) if combined with an antiandrogen or progestogen as these agents will help with testosterone suppression. Similarly, doses should be lower following surgical gonadal removal as testosterone suppression will no longer be necessary.

Estradiol Pellets

Estradiol implants are pellets of pure crystalline hormone and are surgically placed into subcutaneous fat by a physician (Wiki). They are slowly absorbed by the body following implantation, and new implants are given once every 4 to 6 months. Due to the need for minor surgery, their high cost, and limited availability, estradiol implants are not as commonly used as other estradiol routes. Notably, almost all pharmaceutical estradiol implants throughout the world have been discontinued, and the implants that remain available are almost exclusively compounded products provided by compounding pharmacies. Dosage adjustment with estradiol implants is also more difficult than with other estradiol routes. Despite their various practical limitations however, estradiol implants allow for very steady estradiol levels, and their very long duration can allow for unusual convenience among available estradiol forms.

Additional Notes

Table 5: Available forms and recommended doses of estradiol for adulta transfeminine people:

| Medication | Route | Form | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | Oral | Tablets | 2–8 mg/day |

| Sublingual or buccal | Tablets | 0.5–6 mg/dayb | |

| Transdermal | Patches | 50–400 μg/day | |

| Gel | 1.5–6 mg/day | ||

| Sprays | Not recommendedc | ||

| SC implant | Pellet | 25–150 mg/6 months | |

| Estradiol valerate | Oral | Tablets | 3–10 mg/dayd |

| Sublingual or buccal | Tablets | 1–8 mg/dayb,d | |

| IM or SC injection | Oil solution | 0.75–4 mg/5 days; or 1–6 mg/7 days; or 1.5–9 mg/10 days | |

| Estradiol cypionate | IM or SC injection | Oil solution | 1–6 mg/7 days; or 1.5–9 mg/10 days; or 2–12 mg/14 days |

| Aqueous suspension | 0.75–4 mg/5 days; or 1–6 mg/7 days; or 1.5–9 mg/10 days | ||

| Estradiol enanthate | IM or SC injection | Oil solution | 1–6 mg/7 days; or 1.5–9 mg/10 days; or 2–12 mg/14 days |

| Estradiol benzoate | IM or SC injection | Oil solution | 0.15–0.75 mg/day; or 0.3–1.5 mg/2 days; or 0.45–2.25 mg/3 days |

| Estradiol undecylatee | IM or SC injection | Oil solution | 2–12 mg/14 days; or 4–24 mg/28 days; or 6–36 mg/42 days |

| Polyestradiol phosphate | IM injection | Water solution | 40–160 mg/monthf |

a Estradiol doses in pubertal adolescent transfeminine people should be lower to mimic estradiol exposure during normal female puberty (Aly, 2020). b May be advisable to use divided doses 2 to 4 times per day (i.e., once every 6 to 12 hours) instead of once per day (Sam, 2021). c This estradiol form achieves very low estradiol levels at typical doses that don’t appear to be well-suited for transfeminine hormone therapy (Aly, 2020; Graph). d Estradiol valerate contains about 75% of the same amount of estradiol as estradiol so doses are about 1.3-fold higher for the same estradiol levels (Aly, 2019; Sam, 2021). e Doses and intervals for estradiol undecylate are extrapolated and hypothetical (Aly, 2021). f A higher initial loading dose of e.g., 240 or 320 mg polyestradiol phosphate can be used for the first one or two injections to reach steady-state estradiol levels more quickly. However, this preparation has recently been discontinued and appears to no longer be available.

Additional informational resources are available in terms of estradiol levels (Wiki; Table) and approximate equivalent doses (Aly, 2020) with different forms, routes, and doses of estradiol.

There is high variability between individuals in the levels of estradiol achieved during estradiol therapy. That is, estradiol levels during treatment with the same dosage of estradiol can differ substantially between individuals. This variability is greatest with oral and transdermal estradiol but is also considerable even with injectable estradiol preparations and other estradiol forms. As such, estradiol doses are not absolute and should be individualized on a case-by-case basis in conjunction with blood work as a guide. It should also be noted that due to fluctuations in estradiol concentrations with certain routes, levels of estradiol can vary considerably from one blood test to another. This is most notable with sublingual estradiol and injectable estradiol. The fluctuations in estradiol levels with these routes are predictable and must be understood when interpreting blood work results. Differences in blood test results can be minimized with informed and consistent timing of blood draws.

If or when the gonads are surgically removed, testosterone suppression is no longer needed in transfeminine people. As a result, estradiol doses, if they are high or supraphysiological, can be lowered to more closely approximate normal physiological levels in cisgender women.

Progestogens

Progestogens include progesterone and progestins. Progestins are synthetic progestogens derived from structural modification of progesterone or testosterone. There are dozens of different progestins and these progestins can be divided into a variety of different structural classes with varying properties (Table). Examples of some major progestins of different classes include the 17α-hydroxyprogesterone derivative medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera, Depo-Provera), the 19-nortestosterone derivative norethisterone (NET; many brand names), the retroprogesterone derivative dydrogesterone (Duphaston), and the 17α-spirolactone derivative drospirenone (Slynd, Yasmin). Progestins were developed because they have a more favorable disposition in the body than progesterone for use as medications. Only a few clinically used progestins have been employed in transfeminine hormone therapy. However, progestogens largely produce the same progestogenic effects, with a few exceptions, and theoretically almost any progestogen could be used.

Progestogens have antigonadotropic effects via their progestogenic activity and dose-dependently suppress the secretion of the gonadotropins from the pituitary gland. This in turn results in a reduction of gonadotropin-mediated gonadal stimulation and a decrease in sex hormone production as well as fertility. The dose-dependent testosterone-suppressing effects of a variety of different progestogens have been characterized in clinical studies in cisgender men and transfeminine people (Nieschlag, Zitzmann, & Kamischke, 2003; Nieschlag, 2010; Nieschlag & Behre, 2012; Zitzmann et al., 2017; Aly, 2019). Some notable examples of this include cyproterone acetate (CPA) (Aly, 2019; Wiki), MPA (Wiki), NET (Wiki) and its ester norethisterone acetate (NETA) (Wiki), levonorgestrel (LNG) (Zitzmann et al., 2017; Wiki), desogestrel (DSG) (Wu et al., 1999; Wiki), dienogest (DNG) (Meriggiola et al., 2002; Wiki), and progesterone (Wiki), among others. High doses of progestogens by themselves are able to maximally suppress testosterone levels by about 50 to 70% on average (Aly, 2019; Zitzmann et al., 2017 (Graph)). In combination with estrogen however, this increases to about 95%, with testosterone levels suppressed into the normal female range (Aly, 2019). Progestogens seem to usually achieve their maximal testosterone-suppressing capacity at a dose of around 5 to 10 times their ovulation-inhibiting dosage in cisgender women (Aly, 2019). Due to low potency or atypicality, oral progesterone and dydrogesterone are exceptions among progestogens which do not have significant antigonadotropic effects and which would not be expected to suppress testosterone levels (Aly, 2018; Wiki; Wiki).

Besides helping with testosterone suppression, progestogens are of no clear or known benefit for feminization or breast development in transfeminine people. While some transfeminine people anecdotally claim to experience improved breast development with progestogens, an involvement of progestogens in improving breast size or shape is controversial and is not supported by theory nor evidence at present (Wiki; Aly, 2020). It is possible that premature introduction of progestogens, particularly at high doses, could actually have an unfavorable influence on breast development (Aly, 2020). Many transfeminine people have also anecdotally claimed that progestogens have a beneficial effect on their sexual desire. However, a review of the literature by the present author found that neither progesterone nor progestins positively influence sexual desire in humans (Aly, 2020). Instead, the available evidence suggests either a neutral influence or an inhibitory effect of progestogens on sexual desire, although the latter may be specific only to high doses of progestogens (Aly, 2020). Claims have been made that progesterone may have beneficial effects on mood in transfeminine people as well, but clinical support for such notions is likewise lacking at this time (Coleman et al., 2022; Nolan et al., 2022). It is notable that progesterone at luteal-phase levels, due to its neurosteroid metabolites like allopregnanolone, actually appears to worsen mood in around 30% of cisgender women, and produces more overt negative reactions, which constitute the diagnoses of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), in around 2 to 10% of women (Bäckström et al., 2011; Edler Schiller, Schmidt, & Rubinow, 2014; Sundström-Poromaa et al., 2020). More research is needed to evaluate the possible beneficial effects of progestogens in transfeminine people.

Most clinically used progestogens have off-target activities in addition to their progestogenic activity, and these activities may be desirable or undesirable depending on the action in question (Kuhl, 2005; Stanczyk et al., 2013; Wiki; Table). Progesterone has a variety of neurosteroid as well as other activities that can result in central nervous system effects among others which are not shared by progestins. MPA as well as NET and its derivatives have weak androgenic activity, which is unfavorable in the context of transfeminine hormone therapy. NET and certain related progestins produce ethinylestradiol as a metabolite at high doses and hence can produce ethinylestradiol-like estrogenic effects, including increased risk of blood clots and associated cardiovascular problems. Other off-target actions of progestogens include antiandrogenic, glucocorticoid, and antimineralocorticoid activities. These actions can result in differences in therapeutic effectiveness (e.g., androgen suppression or blockade) as well as side effects and health risks. Some notable progestins without undesirable off-target activities (i.e., androgenic or glucocorticoid activity) include low-dose CPA, drospirenone (DRSP), dienogest, nomegestrol acetate (NOMAC), dydrogesterone, and hydroxyprogesterone caproate (OHPC). However, of these progestins, only CPA has been considerably used and studied in transfeminine people.

The addition of progestogens to estrogen therapy has been associated with a number of unfavorable health effects. These include increased risk of blood clots (Wiki; Aly, 2020), coronary heart disease (Wiki), and breast cancer (Wiki; Aly, 2020). High doses of progestogens are also associated with increased risk of certain non-cancerous brain tumors including meningiomas and prolactinomas (Wiki; Aly, 2020). The coronary heart disease risk may be due to changes in blood lipids caused by the weak androgenic activity of certain progestogens, but the rest of the aforementioned risks are probably due to their progestogenic activity (Stanczyk et al., 2013; Jiang & Tian, 2017). Aside from health risks, progestogens have also been associated with adverse mood changes (Wiki; Wiki). However, besides the case of progesterone and its neurosteroid metabolites, these effects of progestogens are controversial and are not well-supported by evidence (Wiki; Wiki). Progestogens are otherwise generally well-tolerated and are regarded as producing little in the way of side effects.

In contrast to certain progestins, progesterone has no unfavorable off-target hormonal activities. Due to its lack of androgenic activity, progesterone has no adverse influence on blood lipids and is not expected to raise the risk of coronary heart disease. The addition of oral progesterone to estrogen therapy notably has not been associated with increased risk of blood clots (Wiki). In addition, oral progesterone seems to have less risk of breast cancer than progestins with shorter-term therapy, although this is notably not the case with longer-term exposure (Wiki; Aly, 2020). Consequently, it has been suggested that progesterone, for reasons that have yet to be fully elucidated, may be a safer progestogen than progestins and that it should be the preferred progestogen for hormone therapy in cisgender women and transfeminine people. However, there are also theoretical arguments against such notions. Oral progesterone is known to produce very low progesterone levels and to have only weak progestogenic effects at typical doses (Aly, 2018; Wiki). The seemingly better safety of oral progesterone may simply be an artifact of the low progesterone levels that occur with it, and hence of progestogenic dosage. Non-oral progesterone, at doses resulting in physiological and full progestogenic strength, has never been properly evaluated in terms of health outcomes, and may have similar risks as progestins (Aly, 2018; Wiki).

Due to their lack of known influence on feminization and breast development and their known and possible adverse effects and risks, progestogens are not routinely used in transfeminine hormone therapy at present. Major transgender health guidelines note the limitations of the available evidence on progestogens for transfeminine people and have mixed attitudes on their use, either explictly recommending against their use (Coleman et al., 2022—WPATH SOC8), taking a more neutral stance (Hembree et al., 2017—Endocrine Society guidelines), or being permissive of their use (Deutsch, 2016—UCSF guidelines). There is however a very major exception to the preceding in the form of CPA, an antiandrogen which is widely used in transfeminine hormone therapy to suppress testosterone production and which happens to be a powerful progestogen at the typical doses used in transfeminine people. CPA will be described below in the section on antiandrogens. Although progestogens have various health risks, cisgender women of course have progesterone, and the absolute risks of progestogens are very low in healthy young people. Risks like breast cancer also are exposure-dependent and take many years to develop. The testosterone suppression provided by progestogens can furthermore be very useful in transfeminine people, as is widely taken advantage of with CPA. Given these considerations, a limited duration of progestogen therapy in transfeminine people, for instance a few years to help suppress testosterone levels before surgical gonadal removal, may be considered quite acceptable.

Progesterone can be used in transfeminine people by oral administration, sublingual administration, rectal administration, or by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection (Wiki). Progestins are usually used via oral administration, but certain progestins are also available in injectable formulations (Wiki).

Oral Progesterone

Progesterone is most commonly taken orally. It is used by this route in the form of oil-filled capsules containing 100 or 200 mg micronized progesterone under brand names such as Prometrium, Utrogestan, and Microgest (Wiki). Despite its widespread use, levels of progesterone via oral administration have been found using state-of-the-art assays (LC–MS) to be very low (<2 ng/mL [<6.4 nmol/L] at 100 mg/day) and inadequate for satisfactory progestogenic effects in various areas (Aly, 2018; Wiki). In relation to this, even high doses of oral progesterone (400 mg/day) showed no antigonadotropic effect or testosterone suppression in cisgender men (Aly, 2018; Wiki). This is in major contrast to non-oral forms of progesterone and to progestins, which produce dose-dependent and robust testosterone suppression (Aly, 2019; Wiki). In addition to its low progestogenic potency, oral progesterone is excessively converted into neurosteroid metabolites like allopregnanolone and pregnanolone. These metabolites act as potent GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators, and can produce undesirable alcohol-like side effects such as sedation, cognitive, memory, and motor impairment, and mood changes (Wiki; Wiki). As such, while inconvenient, non-oral routes are greatly preferable for progesterone.

Sublingual Progesterone

Sublingual progesterone tablets exist and are marketed under the brand name Luteina but today are only available in Poland and Ukraine (Wiki). Oral progesterone could theoretically be taken sublingually, analogously to sublingual use of oral estradiol. However, because oral progesterone is formulated as oil-filled capsules, this makes it difficult and unpleasant to use by sublingual administration. Buccal progesterone, which would be expected to have similar characteristics to those of sublingual progesterone, has been used in medicine in the past, but is no longer marketed today (Wiki).

Rectal Progesterone

Progesterone is approved for use by rectal administration in the form of suppositories under the brand name Cyclogest (Wiki). This product is marketed in only a limited number of countries however, although it is available in the United Kingdom (Wiki). While not approved for use by rectal administration, oral progesterone capsules can be taken rectally instead of orally, and using them in this way may allow for much higher progesterone levels than would be achieved by oral administration due to avoidance of most first-pass metabolism. Rectal administration of oral progesterone capsules has not been formally studied, but oral progesterone capsules have been administered vaginally in cisgender women with success (Miles et al., 1994; Wang et al., 2019), and the vaginal and rectal routes are said to have similar pharmacokinetics in general (Goletiani, Keith, & Gorsky, 2007; Wiki). Hence, there is good theoretical basis for rectal administration of oral progesterone capsules being an effective route of progesterone. Whereas oral progesterone achieves very low levels of progesterone, rectal progesterone can readily achieve normal luteal-phase levels of progesterone (Wiki). Although inconvenient, rectal administration may be the overall best route of administration of progesterone for transfeminine people. A significant subset of transfeminine people on progestogens take progesterone rectally (Chang et al., 2024).

Injectable Progesterone

Progesterone by injection is available as an oil solution for intramuscular injection under brand names such as Proluton, Progestaject, and Gestone (Wiki) and as an aqueous solution for subcutaneous injection under the brand name Prolutex (Wiki). Oil solutions of progesterone for intramuscular injection are widely available, whereas the aqueous solution of progesterone for subcutaneous injection is available only in some European countries (Wiki). Injectable progesterone, regardless of route, has a relatively short duration and must be injected once every one to three days (Wiki; Wiki). This makes it too inconvenient to use for most people. Unlike with estradiol, progesterone esters with longer durations than progesterone itself by injection are not chemically possible as progesterone has no hydroxyl groups available for esterification (Wiki). Injectable aqueous suspensions of microcrystalline progesterone were previously marketed and had a duration of 1 to 2 weeks, but these preparations were associated with pain at the injection site and were eventually discontinued (Aly, 2019; Wiki).

Other Progesterone Routes

Other progesterone routes, such as transdermal progesterone and subcutaneous progesterone pellets, are also known, but are not available as pharmaceutical drugs and are little-used medically (Wiki). This is related to the low potency of progesterone and difficulty achieving progesterone levels high enough for adequate therapeutic effects with these routes (Wiki; Wiki). In addition, progesterone pellets tend to be extruded at high rates (Wiki). In any case, certain compounding pharmacies may make forms of progesterone that could be used by these routes.

Oral and Injectable Progestins

Most progestins are taken orally in the form of solid tablets (Wiki). In contrast to progesterone, progestins, owing to their synthetic nature, are resistant to metabolism in the intestines and liver and have high oral bioavailability. In addition, unlike the case of the estrogen receptors, the progesterone receptors are expressed minimally or not at all in the liver, and there is no known first pass influence of progestogenic activity on liver synthesis (Lax, 1987; Stanczyk, Mathews, & Cortessis, 2017). As a result, there are no apparent problems with oral administration in the case of purely progestogenic progestins. However, some progestins have liver-impacting off-target hormonal actions, such as androgenic, estrogenic, and/or glucocorticoid activity, and this can result in adverse effects like unfavorable lipid changes or procoagulation—which may be augmented by the first pass with oral administration.

A selection of progestins are available in injectable formulations, including for intramuscular or subcutaneous injection (Wiki). Some of the more notable ones include medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), norethisterone enanthate (NETE), hydroxyprogesterone caproate (OHPC), and algestone acetophenide (dihydroxyprogesterone acetophenide; DHPA) (Wiki). In addition to being used alone, injectable progestins are used together with estradiol esters in combined injectable contraceptives (Wiki). These preparations are often used as a means of hormone therapy by transfeminine people in Latin America. Whereas injectable progesterone has a duration measured in days, injectable progestins have durations ranging from weeks to months, and can be injected much less often in comparison (Table).

Additional Notes

Table 6: Available forms and recommended doses of progestogens for transfeminine people:

| Medication | Route | Form | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | Oral | Oil-filled capsules | 100–300 mg 1–2x/day |

| Rectal | Suppositories; Oil-filled capsules | 100–200 mg 1–2x/day | |

| IM injection | Oil solution | 25–75 mg/1–3 days | |

| SC injection | Water solution | 25 mg/day | |

| Progestins | Oral; IM or SC injection | Tablets; Oil solution; Water solution | Various |

For progesterone levels with different forms, routes, and doses of progesterone, see the table here (only LC–MS and IA + CS assays for oral progesterone) and the graphs here.

As with estradiol, there is high variability between individuals in progesterone levels. Conversely, there is less variability between individuals in the case of progestins.

After removal of the gonads, progestogen doses can be lowered or adjusted to approximate normal female physiological exposure or they can be discontinued entirely.

Antiandrogens

Aside from estrogens and progestogens, there is another class of hormonal medications used in transfeminine hormone therapy known as antiandrogens (AAs). These medications reduce the effects of androgens in the body by either decreasing androgen production and thereby lowering androgen levels or by directly blocking the actions of androgens. They work via a variety of different mechanisms of action, and include androgen receptor antagonists, antigonadotropins, and androgen synthesis inhibitors.

Androgen receptor antagonists act by directly blocking the effects of androgens, including testosterone, DHT, and other androgens, at the level of their biological target. They bind to the androgen receptor without activating it, thereby displacing androgens from the receptor. Due to the nature of their mechanism of action as competitive blockers of androgens, the antiandrogenic efficacy of androgen receptor antagonists is both highly dose-dependent and fundamentally dependent on testosterone levels. They do not act by lowering testosterone levels, although some androgen receptor antagonists may have additional antiandrogenic actions that result in decreased testosterone levels. Because androgen receptor antagonists do not work by lowering testosterone levels, blood work can be less informative for them compared to antiandrogens that suppress testosterone levels. Androgen receptor antagonists include steroidal antiandrogens (SAAs) like spironolactone (Aldactone) and cyproterone acetate (CPA; Androcur) and nonsteroidal antiandrogens (NSAAs) like bicalutamide (Casodex).

Antigonadotropins suppress the gonadal production of androgens by inhibiting the GnRH-mediated secretion of gonadotropins from the pituitary gland. They include estrogens and progestogens. In addition, GnRH agonists such as leuprorelin (Lupron) and GnRH antagonists such as elagolix (Orilissa) act similarly and could likewise be described as antigonadotropins.

Androgen synthesis inhibitors inhibit the enzyme-mediated synthesis of androgens. They include 5α-reductase inhibitors (5α-RIs) like finasteride (Propecia) and dutasteride (Avodart). There are also other types of androgen synthesis inhibitors, for instance potent 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase inhibitors like ketoconazole (Nizoral) and abiraterone acetate (Zytiga). However, these agents have limitations (e.g., toxicity, high cost, and lack of experience) and have not been used in transfeminine hormone therapy.

Although antigonadotropins and androgen synthesis inhibitors have antiandrogenic effects secondary to decreased androgen levels, they are not usually referred to as “antiandrogens”. Instead, this term is most commonly reserved to refer specifically to androgen receptor antagonists. However, antigonadotropins and androgen synthesis inhibitors may nonetheless be described as antiandrogens as well.

After removal of the gonads, antiandrogens can be discontinued. If unwanted androgen-dependent symptoms, such as acne, seborrhea, or scalp hair loss, persist despite full suppression or ablation of gonadal testosterone, then a lower dose of an androgen receptor antagonist, such as 100 to 200 mg/day spironolactone or 12.5 to 25 mg/day bicalutamide, can be continued to treat these symptoms.

Table 7: Available forms and recommended doses of antiandrogens for transfeminine people:

| Medication | Type | Route | Form | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyproterone acetate | Progestogen; Androgen receptor antagonist | Oral | Tablets | 2.5–12.5 mg/daya |

| Spironolactone | Androgen receptor antagonist; Weak androgen synthesis inhibitor | Oral | Tablets | 100–400 mg/dayb,c |

| Bicalutamide | Androgen receptor antagonist | Oral | Tablets | 12.5–50 mg/dayb |

a For CPA, this dose range is specifically one-quarter of a 10-mg tablet to one full 10-mg tablet per day (2.5–10 mg/day) or a quarter of a 50-mg tablet every other day or every 2 to 3 days (4.2–12.5 mg/day). A dosage of 5–10 mg/day or 6.25–12.5 mg/day is likely to ensure maximal testosterone suppression, while lower doses may be less effective (Aly, 2019). b For spironolactone and bicalutamide, it is assumed that testosterone levels are substantially suppressed (≤200 ng/dL [<6.9 nmol/L]). If testosterone levels are not suppressed to this range, then higher doses may be warranted. c Spironolactone and its metabolites have relatively short half-lives, and twice-daily administration in divided doses (e.g., 100–200 mg twice per day) is recommended.

|

|---|

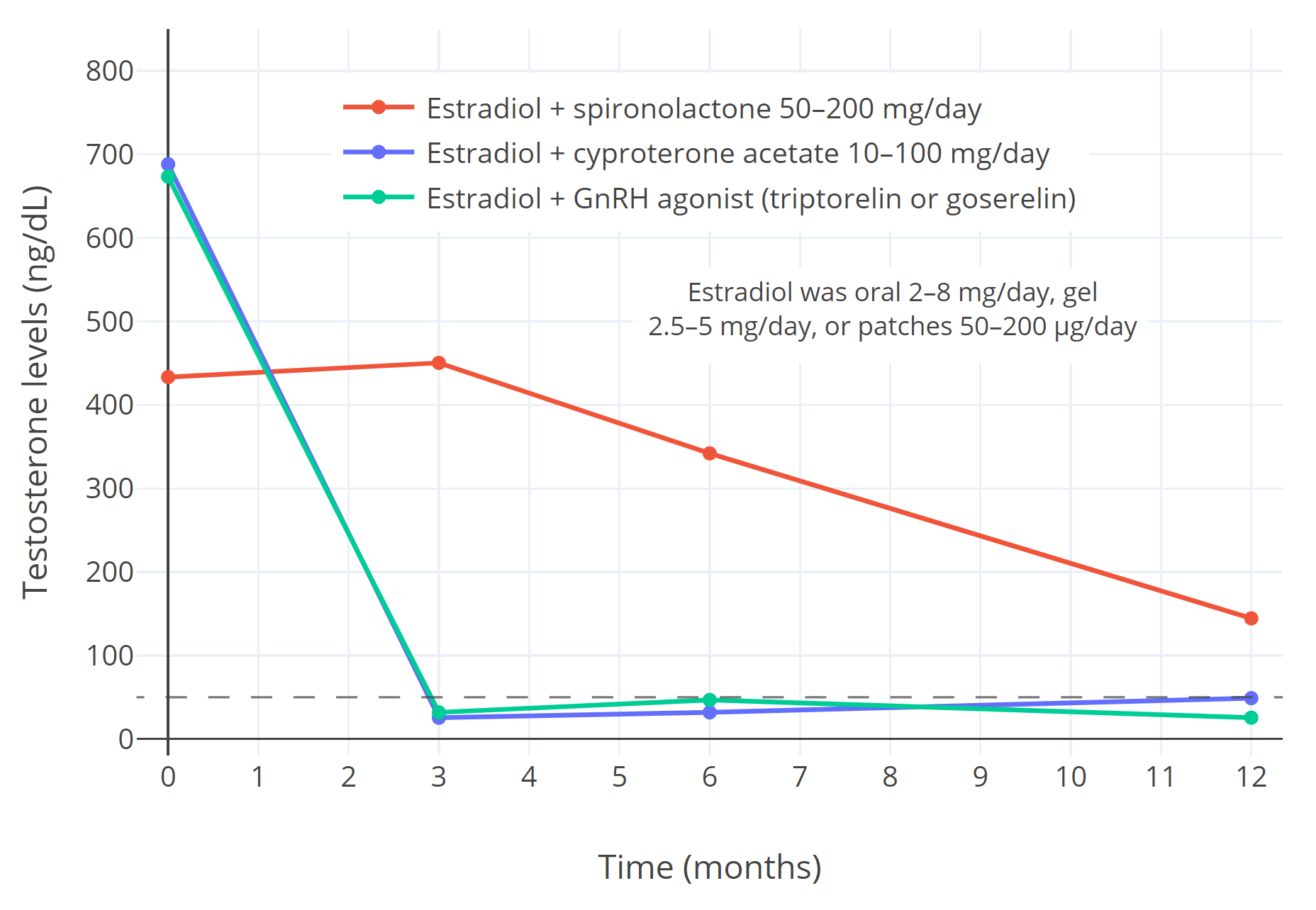

| Figure 3: Suppression of gonadal testosterone production and circulating testosterone levels (ng/dL) with estradiol in combination with different antiandrogens over one year of hormone therapy in transfeminine people (Sofer et al., 2020). The estradiol forms included oral tablets 2–8 mg/day, transdermal gel 2.5–5 mg/day, and transdermal patches 50–200 μg/day. The antiandrogens included spironolactone 50–200 mg/day (n=16), cyproterone acetate (n=41), and GnRH agonists (specifically triptorelin 3.75 mg/month or goserelin 3.6 mg/month by injection) (n=10) (Sofer et al., 2020). It should be noted that lower doses of cyproterone acetate (10–12.5 mg/day) show equal testosterone suppression to higher doses (25–100 mg/day) and higher doses should no longer be used (Aly, 2019). The dashed horizontal line corresponds to the upper limit of the normal female range for testosterone levels. |

Cyproterone Acetate

Cyproterone acetate (CPA; Androcur) is a progestogen and antiandrogen. It is widely used as a progestogen in cisgender women, including in hormonal birth control and menopausal hormone therapy. CPA is also widely used as an antiandrogen in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions in cisgender women and cisgender men. In cisgender women, it is used to treat acne, hirsutism (excessive facial/body hair growth), scalp hair loss, and hyperandrogenism (high androgen levels) due to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). In cisgender men, it is used to treat prostate cancer and to lower sex drive in the management of sexual problems such as paraphilias, hypersexuality, and sex offenses. Besides cisgender people, CPA is widely used as a component of hormone therapy—specifically as an antiandrogen—in transfeminine people. The medication is notably not marketed in the United States, where spironolactone is most commonly used instead. However, CPA is widely available throughout the rest of the world, and is the most frequently used antiandrogen in transfeminine people in Europe and probably the whole world overall (T’Sjoen et al., 2019; Glintborg et al., 2021; Coleman et al., 2022).

As an antiandrogen, CPA has a dual mechanism of action of suppressing testosterone levels via its progestogenic and hence antigonadotropic activity and of acting as an androgen receptor antagonist (Aly, 2019). The progestogenic activity of CPA is of far greater potency than its androgen receptor antagonism however (Aly, 2019). The dose of CPA used as a progestogen in cisgender women is about 2 mg per day, which produces similar progestogenic effects to those of physiological luteal-phase levels of progesterone (e.g., suppression of gonadotropin secretion, ovulation inhibition, and endometrial transformation and protection) (Aly, 2019). Conversely, much higher doses of CPA of 50 to 300 mg/day have typically been used for androgen-dependent indications (Aly, 2019). These high doses of CPA result in profound progestogenic overdosage and associated side effects and risks (Aly, 2019). In transfeminine people, CPA has historically been used at doses of 50 to 150 mg/day (Aly, 2019). However, CPA doses have dramatically fallen in recent years, and today doses of no more than 10 to 12.5 mg/day are recommended (Aly, 2019; Coleman et al., 2022—WPATH SOC8). These lower doses of CPA still produce strong progestogenic effects, and in combination with estradiol, are equally effective as higher doses in suppressing testosterone levels (Aly, 2019; Meyer et al., 2020; Even Zohar et al., 2021; Kuijpers et al., 2021; Coleman et al., 2022). Even lower doses of CPA, for instance 5 to 6.25 mg/day, are currently being studied, and may still be fully effective (Aly, 2019).

Given by itself without estrogen, CPA typically suppresses testosterone levels in people with testes by about 50 to 70%, down to about 150 to 300 ng/dL (5.2–10.4 nmol/L) (Meriggiola et al., 2002; Toorians et al., 2003; Giltay et al., 2004; T’Sjoen et al., 2005; Tack et al., 2017; Zitzmann et al., 2017; Aly, 2019). Lower doses of CPA alone (e.g., 10 mg/day) show the same degree of testosterone suppression as higher doses of CPA alone (e.g., 50–100 mg/day), indicating that the antigonadotropic effects of CPA are maximal at relatively low therapeutic doses of this medication (Aly, 2019). This is on the order of about 5 to 10 times the ovulation-inhibiting dosage of CPA in cisgender women, a dose–response relationship that has also been observed with a number of other progestogens (Aly, 2019). Per the preceding, CPA alone, regardless of dosage, is unable to reduce testosterone levels into the normal female range (<50 ng/dL [<1.7 nmol/L]). But when CPA is combined with estradiol, even at relatively small doses of estradiol, it consistently suppresses testosterone levels into the normal female range (Aly, 2019; Angus et al., 2019; Gava et al., 2020; Sofer et al., 2020; Collet et al., 2022). However, it appears that a certain minimum level of estradiol, perhaps around 60 pg/mL (220 pmol/L) on average, is required for this to occur (Aly, 2019). Estradiol levels lower than this threshold in those taking CPA, which can occasionally be encountered in transfeminine people due to estradiol being dosed too low, have the potential to compromise full testosterone suppression (Aly, 2019).